Blood Sugar 140: Context is Everything II: The OGTT

In the last installment, I discussed the context of blood glucose readings over 140 mg/dL in diabetics vs. non-diabetics. In this installment I'm going to discuss it in the context of an Oral Glucose Tolerance Test, OGTT. The crux of this post is that the results of this study do not justify the Ruhl/Jaminet/(and I'll add Kresser) takeaway message vis a vis diabetes complications and "spikes" in blood glucose. The fact that 50% of the neuropathy subjects to whom OGTT's were administered had 2 hr. glucose levels over 140 (e.g. diagnosed as Impaired Glucose Tolerance, IGT) simply does not support: Nerve Damage Occurs when Blood Sugars Rise Over 140 mg/dl (7.8 mmol/L) After Meals as stated on Ruhl's site and in Perfect Health Diet (Kindle Locations

712-716). (This seems to have been repeated by Chris Kresser as well).

What

is an OGTT? The most common form is conducted

in the fasted state, at least 8 hrs, studies seem to favor 10 or 12 hrs. It involves ingesting 75g of liquid glucose

solution in a short period of time. Glucose (and often insulin) levels are sampled

at 30 min (sometimes shorter at early time periods) intervals for 2 to 3

hours. There are two values that are assessed:

- 1 hour and/or peak BG: under 200 mg/dL = normal , 200 mg/dL or over = IGT or diabetic

- 2 hour BG: under 140 mg/dL = normal, 140-199 mg/dL = IGT, 200 mg/dL or over = diabetic

I looked for some summary OGTT plots and couldn't find anything in short order, but found this plot posted on the Joslin diabetes forums. (No love on tineye.com to track down the original source of this plot, any assistance greatly appreciated.) This is apparently for older,

overweight non-diabetics (that description might make one wonder if

these were not "normal", but the average individual was back to 100

mg/dL by the 2 hr. mark). Even the upper end group was back to 115

mg/dL down from an average peak of 170 mg/dl. Another

way to look at this data is to look across the 140 mg/dL line. The

lower end group spent ~37.5 minutes over 140 mg/dL, the average group

~45 minutes and the high end group ~67.5 minutes. Forget scientific

studies and all that ... if this amount of elevated glucose would cause

damage that was cumulative, we'd all be gimping along by 30 if not sooner!

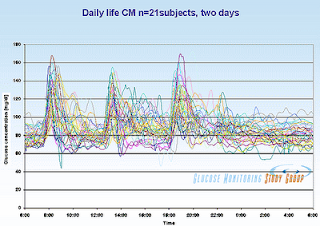

Lastly I repeat this graphic from Ned Koch's post of glucose levels throughout the day for normal sujects. Granted not all seemed to even exceed

the 140 threshold, but many did, repeatedly. The "odd" spike above 140 seems perfectly normal. You will note that it is a "chaotic mess" as Ned describes, but also note that you don't have levels staying high for very long. It's called a "spike" for a reason!

Lastly I repeat this graphic from Ned Koch's post of glucose levels throughout the day for normal sujects. Granted not all seemed to even exceed

the 140 threshold, but many did, repeatedly. The "odd" spike above 140 seems perfectly normal. You will note that it is a "chaotic mess" as Ned describes, but also note that you don't have levels staying high for very long. It's called a "spike" for a reason!

Let's revisit the neuropathy study. To

refresh, it involved 107 subjects, average BMI=29, average age

64, suffering from idiopathic neuropathy. Of this group, a subgroup of

72 had OGTT evaluation. Based on the OGTT results, 50% (36) were

diagnosed IGT based on having a 2 hr. glucose level over 140 mg/dL (an

additional 13 = 18% were diagnosed diabetic). Another finding of the study was that severity of neuropathy correlated with the 2 hr glucose levels in the IGT range.

Bottom Line: A glucose level over 140 mg/dL two hours after an OGTT has no direct relevance to a blood glucose level over 140 mg/dL earlier in the OGTT time course, especially the peak postprandial levels.

The closest the study authors get to implicating the glucose levels per se is:

Bottom Line: A glucose level over 140 mg/dL two hours after an OGTT has no direct relevance to a blood glucose level over 140 mg/dL earlier in the OGTT time course, especially the peak postprandial levels.

The closest the study authors get to implicating the glucose levels per se is:

... Specifically, elevated peak serum glucose level may be a more potent pathogen for peripheral nerves than modestly elevated trough glucose levels....Now they do say "peak", but this isn't really what they studied either, so that is poorly worded in my estimation. In several places they tend towards implicating the underlying metabolic milieu, such as:

... IGT and frank diabetes form a continuum of deranged glucose regulation, and accumulating evidence supports the concept of IGT as a disease entity in its own right. IGT is associated with the syndrome of insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension and is a potent risk factor for cardiovascular and peripheral vascular occlusive disease, independent of IGT risk for diabetes. ...But they don't pursue glucotoxic mechanisms in the discussion. Ultimately this is one of many papers I've come across comparing various diagnostic measures for assessing glucose metabolism and associated risks. There is a lot of evidence that the postprandial challenge -- OGTT results -- are more sensitive to detecting early stages of dysregulated glucose metabolism than are fasting -- FBG -- or long term averages -- HbA1c. Such research will hopefully be considered when developing new diagnostic standards for diabetes with a focus on preventing progression to frank diabetes. I'd also note that this observation would seem to counter those who trace the progression of classic type 2 diabetes through the liver as this etiology would favor FBG as a better predictor.

But that 140 is a biomarker. A value on a standardized test that can help elucidate what's going on. Frankly, as I've mentioned quite a bit lately, I believe an OGTT without concurrent insulin levels is, for lack of a more eloquent term, half-assed. You're collecting blood anyway, why does it not seem to be a matter of course to measure insulin as well? Still, whether due to reduced glucose clearance, as in insulin resistance, or insufficient insulin response, having a BG over 140 at the 2 hour mark for this test is cause for concern. Registering a random BG of 140 is, simply, not.

IMPORTANT NOTE: I'm not trying to downplay the very real issues that IGT and overt diabetes involve. I'm also "with you" looking for earlier measures and markers that might predict future problems and assist us all in taking evasive measures where warranted. If you test your own blood sugar levels and they remain high two hours after eating, then you are IGT and should take this condition seriously. This study presents a compelling case that whatever the mechanism of neuropathy (and other complications), it likely begins in the early stages of IGT, or prediabetes if you will, and perhaps in the "late stages" of normal glucose tolerance. My personal advice, as a non-doctor, non-diabetic, normoglycemic former research scientist who has read so much on this it makes my own head spin? The spike is normal. Look at the shape of OGTT spikes in Ned's graph. What goes up comes down, not quite as fast, but pretty quickly. If your spikes, when you have them, don't look like that, even if they don't leave you with "technically" elevated levels, examine your diet and lifestyle (read: activity level) and work towards improving insulin sensitivity. But normal spikes are just that, normal.

COMING UP: I'm not sure if this series will finish up with one more longer post, or if I'll break it up. I've come across a heckuvalot of new information regarding diabetes and complications and I'm still weighing exactly how to discuss them. Where I am going with this is that complications such as neuropathy vary both in form and severity between different types of diabetes. This would support the hypothesis that such complications are caused by whatever also causes hyperglycemia, and not glucotoxicity per se. For example, one type of genetic diabetes, involves only IFG and IGT where a "diabetes" diagnosis may never be warranted. This mild chronic hyperglycemia (with spikes and slowed clearance) is rarely associated with complications. More to come ...

On a similar note:

Since it's still relatively fresh on my mind and involves OGTT's, I wanted to address a post by Dr. BG about paleo lowering insulin levels based on the 2009 Frasetto study blogged on recently. Dr. BG seems to be in the insulin = bad and carbs => postprandial insulin => hyperinsulinemia camp. One of the more impressive outcomes of that paleo diet -- that excluded all grain, dairy and legumes but included lots of carrot juice, ample fruit and some honey -- was the reduction of insulin secretion on the OGTT. The AUC -- that stands for area under the curve and is a measure of total insulin exposure during the test -- decreased by 32% from 533 to 361 pmol-hr/L. Neither this, nor the even more impressive decrease in fasting insulin of 68% -- from 69 to 21 pmol/L, are directly related to the insulinogenicity of the diets themselves (e.g. the glycemic load). The OGTT is the same 75g glucose for all. However the subjects secreted a lot more insulin to handle the same glucose load before than after following the Frasetto-paleo diet for 10 days (with 1 week modified ramp up). Postprandial insulin is long gone by morning fasting evaluation as well, so this is a baseline. Both of these indicated marked improvements in insulin sensitivity.

While the OGTT results would indicate the subjects likely secreted less insulin to manage their ~250g carb on paleo, they were consuming roughly the same glycemic load so this was not due to stimulating a lower insulin response gram-wise. One might argue over the GI of the diet, but I would point out that such things as carrot juice and pineapple would be rather higher GI. In any case, the OGTT's involved the same 75g glucose but the paleo dieters required less insulin to handle it. This is not the same as saying that the paleo diet lowers insulin levels by stimulating less insulin per glycemic load. So this is another example of taking the OGTT results out of context. What they demonstrated was how the diet composition indirectly -- by enhancing insulin sensitivity -- improved insulin levels independently from expected carbohydrate induced spikes.

Comments

The diet was high in natural sugars, and sugars typically do have a lower glycemic index than starch since they're 50% fructose. Not that I think that had much to do with the outcome...

I think diabetes is a major clue here. I read about how eating a diet both low calorie and low carbohydrate for 60 days seemed to reverse type 2 (for 3 months, anyway). This seems to point to overeating, but the question would be "what is causing the overeating?" Although I think Stephan Guyenet is on the right track, I also think it's clear that the answer is going to be difficult to isolate.

So how does eating food lead to diabetes? That is a very good question.

I wonder if there are experiments where forced overeating for an extended period of time induced diabetes. This would explain how diabetes is related to the quantity of food eaten, but it would not explain what initially caused the overeating.

Yeah, this diet was lower GI, and lower GL for glucose, but pineapple, cantaloupe and carrot sugars are mostly sucrose (according to nutritiondata.com) with a bit of starch in carrots. Roughly 1/2 and 1/2 glucose:fructose. But OTOH, we're talking juicy fruits and juiced carrots where we're told the "rapid delivery" is an issue. Interesting, we're either talking a pretty decent fructose load (they were ramped up with some orange juice for a week as well), and/or glycemic load if Sievenpiper's values for the fate of fructose are accurate.

'This study demonstrates for the first time the time course of a return of normal beta cell function and hepatic glucose output by acute restriction of dietary energy intake in individuals with type 2 diabetes. The changes occurred in association with decreases in pancreatic and liver triacylglycerol concentrations. This new insight allows an understanding of the causality of type 2 diabetes in individuals as well as in populations.'

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.02992.x/pdf

'Whereas the incretin hormones achieve fine regulation,

substrate supply drives metabolism. The basic metabolic fact

has been overlooked that the restriction of calorie intake which necessarily follows bariatric surgery will bring about a rapid decrease in the fatty liver typical of Type 2 diabetes. The degree of restriction relates to the extent of the surgical procedure. Even moderate dietary restriction is associated with profound change in hepatic insulin sensitivity and marked fall in hepatic glucose output early during a hypocaloric diet. The associated time course of decrease in liver volume is over days. Conversely, the period before onset of Type 2 diabetes is characterized by accumulation of liver fat.'

I've blogged on the study cited in one of euler's links several times (look in chronological order post for crash diet). Similar has been seen with early insulin treatment in T2's. I'm partial to an "overwhelmed beta cell" model than the exhausted pancreas one.

If the Kitava diet (or a close analog) is fed to children of mixed racial profiles from birth, would it have the same effect on these people even if they have a genetic predispositions to type 2 diabetes, heart disease, cancer, obesity, etc.?

There are some very intriguing advantages to being vegetarian (in my opinion). The Kitava diet is as close as I would care to alter my diet in that direction. Every time I try and imagine the problems stem from grains and dairy, I remember the French paradox and I'm mostly back at square one.

I think your "overwhelmed beta cell" idea may be correct. However, even if the cause is genetic the etiology still needs to be explained.

What do practitioners like Steve Parker & Richard Bernstein have to say ?

Now, if ONLY there were a rat-animal or mouse-animal study, all would be clearer.

Were I a practicing diabetic who regularly tracked post meal BG levels, I would also look at 3-montthly HbA1c. ONLY if HbA1c values were >= 5.5% and the AUC of (BG >= 140) was not negligible, would I be much interested.

Finally, the psychology of the sufferer plays a role:

Is one a "glass 1/3rd empty, or 2/3rds full" person ?

Slainte

If they have a few post-meal spikes and all other markers or normal, I'm not concerned. If their fasting BG, A1c and fructosamine are all elevated, and they're having spikes, then I'm concerned and I will investigate further.

On a similar note, I've written that A1c is not a reliable marker for individuals because of context: there are many non-blood sugar-related conditions that can make A1c appear high or low. So if someone is normal on all of the other blood sugar markers, but has high A1c, I'm usually not concerned.

I should probably make this context piece more clear in the article I wrote about post-meal blood sugars a while back.

I'm on an antiphobia kick lately :D And this 140 mg/dL taken out of context has been the source of glucophobia in the LC circles for a good long time. I REALLY don't get Bernstein and Davis taking it to extremes saying that BG shouldn't even spike!

Post a Comment

Comment Moderation is ON ... I will NOT be routinely reviewing or publishing comments at this time..